On February 2, 1984, a family in Ann Arbor, Michigan, lost their 14-year-old son to massive head injuries. I know, because on the evening of February 2, 1984, my husband, Bill, received a phone call from Dr. Chip Bolman. He said, “I think we have a donor. How soon can you be in Minneapolis?” We had waited for that call for what seemed to be years. However, it had been only three weeks since Bill had been put on the waiting list at the University of Minnesota Hospitals for a heart transplant.

Bill had a condition called ischemic cardiomyopathy. In plain English, that means his heart was no longer able to pump sufficient quantities of blood. Normal/average pumping capacity falls somewhere around 70%. Bill’s pumping capacity was at 11% - 17%. This condition was brought about by a series of six heart attacks. The first one struck at age 31, on September 15, 1977. Then in June, 1981, June 25, 1982, October, 1982, April, 1983 and a silent heart attack sometime in November 1983. There were intermittent bouts with heart failure and hospitalizations between the heart attacks. It was all presumably caused by arteriosclerotic heart disease – blockages in the arteries that supply the heart with blood.

Bill was never a candidate for bypass surgery. After each heart attack, an angiogram was performed. Each time, the angiogram would show no other blockages in any remaining arteries. One by one, each artery would shut down and all of the other arteries were always clear/clean, showing no reason for surgery.

Finally, there was one artery left, the occidental – inoperable.

After several bouts with heart failure during late fall of 1983, a decision was made to determine whether there was bypass surgery of any kind that might be helpful and if it would be possible to resect an aneurysm that had developed on the left ventricle. Another angiogram was scheduled for December 12, 1983, to better define the exact condition of Bill’s heart. He’d had five uneventful angiograms before, so we both thought we knew what was coming. We were wrong.

When Dr. Wheeler, Bill’s cardiologist, appeared from the catheterization lab, he looked more serious than I had ever seen him before. He said Bill’s heart was far too severely damaged for surgery; there was not enough live tissue left to save. The only alternative was a heart transplant. Would we consider that? There was no question in our minds. Bill and I had discussed that possibility, but had hoped it would not be necessary so soon. Dr. Wheeler said he thought Bill could be kept alive two months, maybe three. (Counting from mid-December - three months would be mid-March.)

Then he told us that Bill had had a cardiac arrest during the angiogram. His weakened heart couldn’t handle the added stress of the catheterization. He had been revived and was breathing normally, though he was extremely weak. I could see the pain in Dr. Wheeler’s eyes. He had taken care of Bill many times before; he would now make the plan that would save Bill’s life.

I went to Bill’s side as he was wheeled out into the hall from the cath lab. “I guess I was out for a few minutes, babe,” he whispered. Afterward, he was taken to ICU. I told him he had to be strong, to keep fighting, that there was still a chance with the transplant. He said, “I’ll keep fighting, honey; I’ll try.”

I swear to God, Bill had an unflappable sense of humor. Even after a cardiac arrest. In the ICU, recovering from a heart cath and subsequent cardiac arrest, he opened one eye, looked straight at me, and said, “Maybe I’ll get a Black heart.” I responded, “Maybe, you would. Would you mind?” Then he closed that eye, waited a minute or two, then opened it again. “Hell, no! Maybe it’ll give me a little rhythm.” Then a little smile crept across his mouth. He was a great slow dancer, but anything faster called for two left feet to make an appearance. (Incidentally, we don’t know the race of his donor, but his dancing didn’t improve.)

Ultimately, it was Bill’s attitude, his unyielding determination to live, that supported us all. While other kids were worrying about Saturday night dates or math tests, our children, Matt, age 17, and Rachel, age 14, were sitting in emergency rooms or waving good-bye to Dad in the LifeFlight helicopter. I was working full time at a bank in our home town. With six heart attacks, his work life was intermittent. He insisted life go on as normally as possible – always doing as much as he could. However, six heart attacks, four in two years, created a state of constant crisis in our home.

These were junior and senior high school years for our children. These years already have built-in complications of their own. These are years during which home should be a stabilizing, calming influence. Instead, life was a roller coaster of emotions at our house.

Bill spent most of the rest of December 1983, in Mercy Hospital in Des Moines. Bill’s parents and I stayed in Des Moines to be with him. Matt stayed at home alone, with my mother and brother looking in on him. Rachel stayed with my brother, Joe and his wife, Sharon and their family. I don’t know what we would have done without the help of both of our families that Christmas season. Bill’s brother’s wife, Vicki, bought all the rest of the presents I didn’t have the time or heart to buy. Sharon, my brother’s wife, took care of Rachel as if she were her own.

Dr. Wheeler said Bill would be able to come home for Christmas. I came home a few days before Christmas. The weather was bitterly cold and the streets and highways were slick with ice. A 70-mile trip home took over three hours that day. Nevertheless, I needed to look at the mail, pay bills, and make last minute preparations.

I wanted it to be special. Aside from Christmas, Bill’s birthday was December 25 and our anniversary was December 26. It was a time heavy with emotions.

Bill was discharged on December 24, but ended up in a motel near the hospital with his parents because of a winter storm. The kids and I tried, but it wasn’t a very happy Christmas Eve, the first we’d ever spent without Bill. By this time, word had spread around our little town about what we were facing. One friend brought a ham to our door, speechless, with tears in his eyes. Others stopped by with Christmas cookies and candy.

Thanks to Bob Walker, a classmate and rep with an insurance company, a fund was started to defray expenses not covered by insurance. There was a fund-raiser pot-luck dinner to be held, which we had intended to attend. As it turned out, the dinner was held just a couple of days after he had the transplant. Instead of attending, we received so many cards and one great big banner signed by everyone who attended. Even now, so many months and years later, my eyes fill with tears when I think of the many kindnesses and the unending support shown to us.

Bill’s parents drove Bill home on Christmas morning. Friends of ours living in Des Moines, also going to our home town for the holidays, followed them all the way home, to be available in the event of accident or other issues. The wind was so strong, when they stopped the car to help Bill into his parents’ car at the motel, the wind blew our friends’ car door inside out, and the hinges were sprung. When Bill arrived home, we celebrated with a quiet dinner and opened presents. We even had birthday cake for Bill’s 38th birthday.

We took pictures that later were very upsetting to Bill; he didn’t realize how bad, how really sick and thin, he looked then.

On December 27, the four of us, Bill and I and his parents, drove to Minneapolis for Bill to begin the transplant evaluation. Many tests were to be done to decide if Bill would be a good candidate for a transplant. He was so sick by then, so sick and colorless; there were days I wondered if he would make it through the evaluation. They allowed him to come home on the 29th, due to the long holiday weekend. He was so sick of hospitals and so glad to be home. However, on New Year’s Eve, he was again admitted to our local hospital because of heart failure. He stabilized quickly, but was depressed about spending more time in another hospital on another holiday.

Dr. Anil Sahai, Bill’s internist, was out of town that night. His brother, Dr. Subhash Sahai, was taking care of Bill and sensed the situation. He brought a bottle of champagne to Bill’s room, and permitted Bill one ounce of champagne to welcome 1984. It was served in a little plastic pill cup. The kind of cap on cough syrup bottles. Bill didn’t finish the ounce, but drank completely of the humanity of the doctor who had prescribed it. When the body is put through so much, the human being is often lost.

The testing began again at the University Hospitals in Minnesota on January 3, 1984. Bill was becoming weaker, more uncomfortable every day. On Friday, January 13, his name was placed on the waiting list and he was discharged. By now, he was taking 19 different kinds of medication, about every 6 hours; roughly 43 pills a day. He was relieved to be at home and was hoping to have a few weeks to rest and be with his family. His unfailing optimism continued. He simply did not allow for the possibility that a donor might not be found in time. That was a very difficult time in many ways, of course. I kept my eye on the calendar. We were now 1/3 of the way through the three months on the outside that Dr. Wheeler had given Bill to live.

What stands out now is the horrible contradiction we felt about waiting for someone to die so that he could live. A doctor told us, “That person will die anyway. You’re waiting only to let that person’s heart live on.”

He refused to have anyone stay with him while I was at work and the kids were back at school after Christmas break. His heart would tolerate his getting dressed, walking from the bedroom to the living room and there he would stay until I came home at lunchtime. He sent the kids off to school and me off to work. “Keep things normal,” he insisted.

Bill’s brother, Spencer, bought him a portable phone (this all happened before cell phones) so he could use the phone without having to get up. His other brother, Bruce and his family, lived hundreds of miles away, but called frequently.

Bill was sitting at the kitchen table with that phone in front of him on Thursday, February 2, 1984, at 6:00 p.m. The phone rang and Bill answered. I was preparing dinner and the kids were watching TV. After he hung up, he said, “They have a donor.” For a few minutes, I couldn’t say anything but, “Oh, my God.” I was happy. I was terrified.

I knew someone, somewhere, had died and his family had given the ultimate gift. Bill had lived long enough to have a chance at a new life.

We had planned for this day very carefully. Spencer and Vicki were called right away to secure air transportation for Bill, the kids and me. They had arranged for several private planes, the owners of which were friends or neighbors and had offered their planes. It turned out the first call they made, to Larry Clement, a car dealer in Fort Dodge, was available that night. He had offered his plane and his services as a pilot. He would meet us at the airport in Fort Dodge, about 25 miles away.

Spencer called Bill’s parents. They had gone out for dinner but had left word of their plans. Everyone in our extended families had gotten into the habit of letting someone know where they would be so they could be reached at a moment’s notice. This was especially important for Matt and Rachel, as we wanted very much for them to be able to fly to the hospital with us to be there before surgery. That wasn’t easy for teenagers, but they cooperated beautifully. As it turned out, they were home that night. I called my brother. He called our mother and Pastor Dave LeMaster. Sharon, my sister-in-law, came over to clean up my half-prepared meal and close up the house after we left.

Another sister-in-law, Vicki called Dr. Sahai and Rosalie Hames, my co-worker so she could advise my boss the next morning. I heard later on that Rosalie also called her husband who was attending a Ducks Unlimited dinner. He made the announcement at the dinner and later they told me everyone cheered. Spencer drove us to the airport about 25 miles away. I don’t think the tires touched the highway.

It’s hard to explain how our little home town of Webster City, Iowa, wrapped its collective arms around our family. There were so many kindnesses that may have gone unacknowledged in the blur of life at that time. And I’m sure there were kindnesses that happened that we didn’t even know about - just something someone might have done to ‘smooth the road.’ But the generosity of heart and soul will live in the memory of our family forever.

All the planning paid off and things went smoothly. We had been living out of half-packed suitcases for three weeks. The call came at six and by seven we were in the plane. Matt had never flown before, so Larry asked him to sit in the co-pilot’s seat. He wore a head set and Larry kept him occupied throughout the flight. Rachel had flown only once as a small child. She was nervous, as were we all. Bill and I sat side-by-side with Rachel facing us. It was a quiet, almost peaceful flight. It was just beginning to snow and the lights on the plane’s wings made the snowflakes sparkle in the darkness. We held hands and looked at each other. Not much was said, but all was understood.

I closed my eyes and remembered how, before we had left home, I stood by the open suitcases and began to cry. Bill put his arms around me and said, “Don’t cry, babe. This is what we’ve been waiting for. It’ll be all right.”

The snow persisted that weekend. Twenty-three people would die on the roads in Minnesota’s third worst storm in history up to that day. But we made it before the worst of the storm, as did our families. Spencer, Vicki, Bill’s parents, my mother and brother and Pastor Dave LeMaster all drove over three hours in snow, on dangerous roads, not knowing whether they’d be able to see Bill before he went into surgery.

Bill was in a room in the Variety Club Heart Hospital, station 201, by 8:40 p.m. Just over 2 1/2 hours since we received the call. Again, the testing began. They took cultures, specimens, and vial after vial of blood. Preliminary matching had been done, but this round of tests would tell the story.

Dr. Chip Bolman, the man who would do the surgery, came in to say hello. He’s an imposing man, tall, good-looking, and young, only 37. Through our experiences with him during the evaluation, after surgery, and through all the months of check-ups, we had come to know him as an uncommonly kind, gentle and compassionate man. I knew the surgery would go long into the night, so I asked him if he had taken time for a nap. The answer was, “No, I tried to find time, but there were too many things to do.”

At 10:30 p.m., Dr. Bolman came back and told us there was a good match. The surgery was on. The surgical team to harvest the heart would be leaving soon for Ann Arbor. By this time, all of our family had arrived safely, including Bill’s brother Bruce and his wife, Darlene, from Illinois. We held hands in a circle and Pastor Dave led us in a prayer. At 11:30 p.m., I stood outside the orange doors leading to surgery, held Bill’s hand, and kissed him. We all kissed him. And later, he told me he didn’t remember any of the kisses. He had already been sedated. I wondered if I’d ever kiss him again. What would this night full of uncertain hope bring?

We walked back down the hall and into the surgical waiting room. It would be a long, sleepless night. I guess we did what everyone else does in waiting rooms. We talked, laughed, cried, drank coffee and soft drinks, ate junk food, drank more coffee and waited and waited and waited. I looked at my watch and wondered what they were doing now. Was he on the heart-lung machine yet? Had they removed his heart? Was he all right?

And what about the family of the boy who had died? I couldn’t imagine what were they feeling now. I looked at our own 14-year-old daughter and felt the pain of another mother.

All I knew then is all I know now. He was a 14-year-old boy from Ann Arbor, Michigan, who had died of head injuries. He had a “good, sturdy heart.” I said prayers for them and their boy then. Now, so many years later, I still think of them occasionally and pray for them and their lost boy.

At the time of their deepest grief, they were able to reach out to others with the gift of life, not only to my husband, but also to the people who were the recipients of the boy’s kidneys and other organs. A total of 7 people that I know of were recipients of this family’s generosity. Surely, God has made a special place in heaven for this little boy and will hold this family in the palm of His hand.

It was 4:20 a.m., Friday, February 3, when a doctor walked into the waiting room. He was a part of the harvesting team. The heart (referred to as “Bill’s second heart”) had arrived at 4:00 a.m. and they would soon be removing Bill’s damaged heart. When the plane had landed in Minneapolis, they called the hospital and the chest incision was made. However, Bill’s heart was not removed until the donor heart was safely in the operating room. The time from 11:30 p.m., February 2, had been spent preparing IVs, hooking up monitors and just plain waiting.

AT 7:55 a.m., February 3, Dr. Bolman came to the waiting room to report, “all is going as expected. Bill is doing well. The heart is beating on its own.” We were relieved beyond words. There were still a hundred things that could go wrong and many hurdles yet to meet. I was bundle of raw nerves, but I knew deep inside that he would make it.

I paced up and down the hall alone by the orange doors where I had stood the night before. At 8:15 a.m., Dr. Bolman appeared again and walked with me to the waiting room, so he could speak to the whole family. “It’s a good heart, a sturdy heart, beating fine. Bill is awake and alert and will be moved to ICU from recovery.” Dr. Bolman would come again to take me to Bill as soon as he was settled.

Finally, at 9:30 a.m., I was able to see Bill. His face was swollen from the heart-lung machine and the large doses of immunosuppressants. He squeezed my hand and moved his feet on command. There were wires and tubes everywhere – six IV pumps, numerous monitors and machines. His arms twitched occasionally as the anesthetic wore off. I had seen much of this kind of paraphernalia before, with each heart attack and with each bout with heart failure. But what I liked the best this time was that heart monitor with its little green line tracking perfect heartbeats. Already, Bill’s complexion was rosier.

Bill doesn’t remember anything about that first day. The next day when the anesthetic was completely gone, the respirator was no longer needed, and the facial swelling was all gone, the first thing he said was, “I can breathe again. And my hands and feet are warm.” He looked like himself again. All the family members were able to take their turns to go in and visit him. We all had to “gown up” wearing surgical gowns and masks. He said, “It’s boring as hell in here when there’s no one to talk to!” We later arranged for a TV and Bill recuperated watching the 1984 Winter Olympics.

Bill was discharged from the hospital on February 21, the 19th day of surgery. We rented a furnished apartment in Minneapolis, expecting to stay for two months, per instructions from Dr. Bolman. As it turned out, we were able to come back home to stay on March 8, with weekly visits to the University Hospitals out-patient clinic.

We found out later that there were daily reports on the local radio station, KQWC, up to his release from the hospital all about Bill’s progress. Things like that he dangled his feet off the edge of the bed on the second day after surgery, how far he walked, what he had for lunch, how the tests were coming out - all thanks to our sister-in-law, Vicki Mickelson, our home town was right there with us.

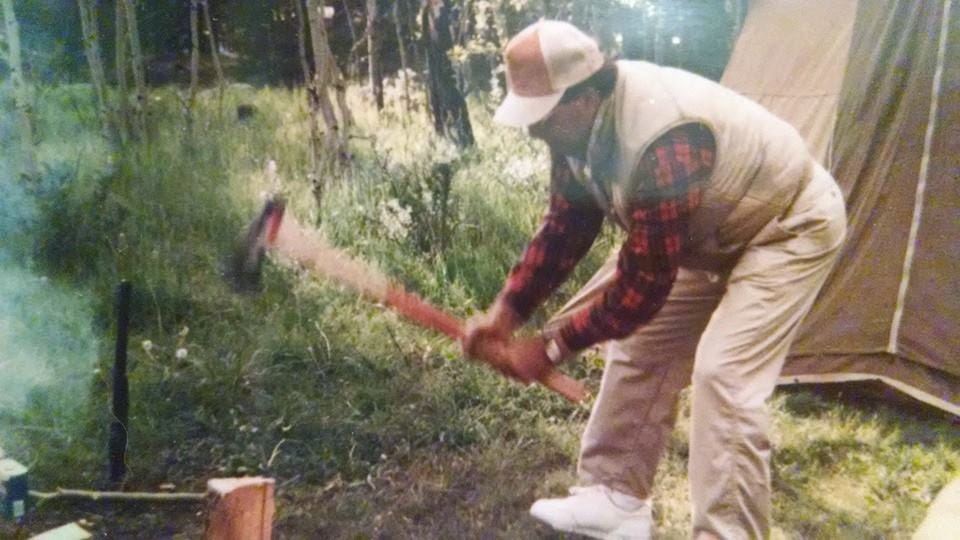

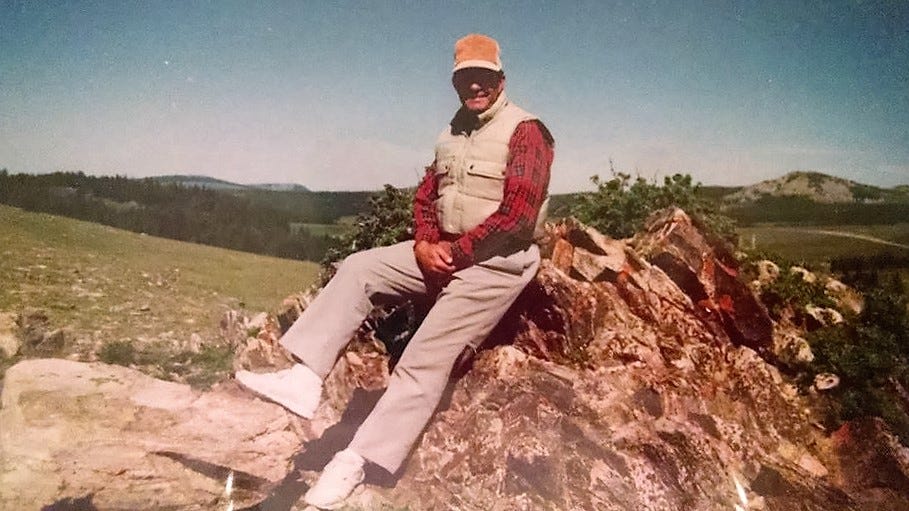

Clinic visits were gradually spaced out. Bill’s case had been turned over from the surgical team to the medical team to further refine dosages and perform biopsies of heart tissue to check for rejection. I had been advised by the medical team of several concerns at home — e.g. no fresh flowers in the house, either I or the kids had to handle the litter box chores, daily vacuuming of carpeted areas and daily scrubbing of hard surface floors. All surfaces he was likely to touch had to be wiped down with liquid Lysol cleaner at least twice a day (no spray would do), including counter and table tops, sink, refrigerator handles, door knobs, telephones, tv remotes - imagine all the things you touch every day. I did that faithfully twice a day as instructed. Finally, when planning the trip described below, I asked the head of the medical team how to handle the Lysol thing while tent camping. She looked at me and said, oh my god, are you still doing that?! Of course, my response was, “no one told me to stop!”. She said, “you can stop, now! And no worries with camping. Just steer clear of snakes and funny looking bugs.”

That summer, we took a vacation to Estes Park, Colorado. How different the summer could have been. After a time, Bill went back to work and our lives were “normal” again. Matt started college in the fall and Rachel started high school. I went back to work at the bank, then ran for, and won a position on the county hospital board. I wanted to give back to the community which had given us so much. In addition, Bill, was my Bill again. He was no longer a desperately ill patient, tethered to medical professionals, to be shared with doctors and nurses and lab technicians, but a whole, happy, healthy, and vibrant man.

Years of research made surgical techniques and immunosuppressant drugs possible. Hospitals have set up transplant teams of cardiologists, surgeons, nurses, social workers and all kinds of technicians. Communities band together to support transplant candidates with funding and prayers and love. Local doctors and nurses fight to keep candidates alive until a donor is available. Nevertheless, without people like the family in Ann Arbor, it would all be for nothing.

I never met the family who gave us Bill’s second heart. I have asked countless times for God’s blessings on that family and that their grief be eased with the knowledge that because of their selfless decision, the lives of countless people have been changed. Also, the lives of the recipients’ families, friends, and communities were enriched by a renewed belief in miracles. Because of their ultimate gift, they gave us all new life.

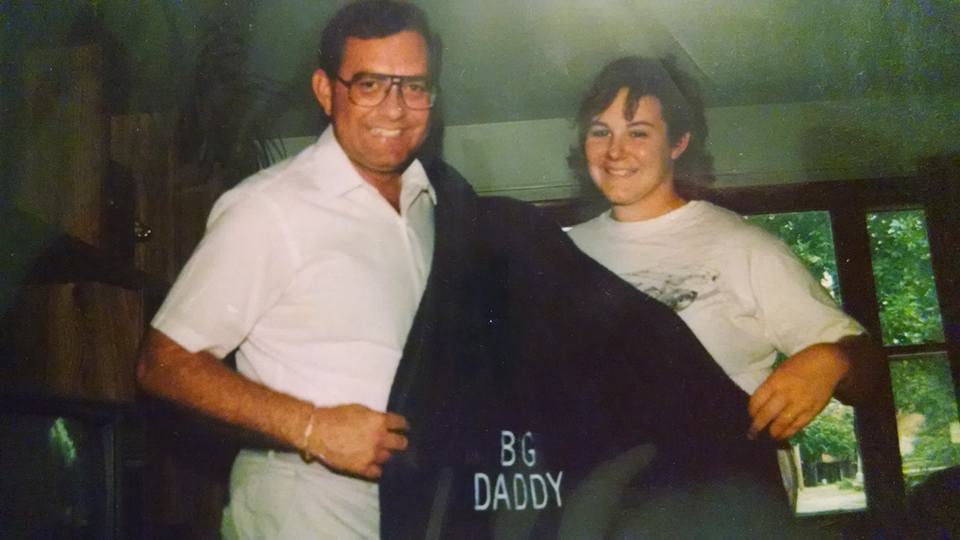

In February, 1994, 10 years after the transplant our family got together to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the miracle that saved his life. Our daughter, Rachel, had a bath towel embroidered with “Big Daddy.”

Bill died a little more than 7 months after that 10th year celebration. It was a complication of the drugs he had to take. He had lived long enough to see both children graduate from school and be married, walking his little girl down the aisle.

We had those 10 wonderful years together, all of which would have been impossible without the many teams of medical professionals who worked so hard to save his life and most importantly, without the family from Ann Arbor, Michigan.

I hope they have felt some comfort in that though modern medicine couldn’t save their young son, their gift saved many other lives. I hope they have found peace over the years. Their son’s heart had stopped beating for the last time. I like to imagine Bill and his donor have already met each other in the afterlife. In any event, the memory of that young boy and his family will live on in the hundreds of hearts of the families and communities touched by their generosity.

Please consider becoming a donor when the time comes. Discuss with your family. And make any necessary decisions in consultation with your doctor and family. You can’t imagine the lives that could be changed with that one decision.

It is the ultimate gift.

I would love to hear your comments on our story, or transplants in general.

My dear Louise-

I am at a loss for many words as I try to respond back to your deep thoughts and message to us. Thru my tears just know how much Bill is loved and to you his beautiful love.

Fondly remembering our favorite Hamilton County Public Hospital patient with the wise crack jokes and smirks.

Luv ya my friend,

Bert

( I am a registered donor)